Japanese Theater is one of the oldest and most sophisticated branches of the world’s performing arts, which is still very exciting in Japan, and one of the tourist attractions of this country is to watch one of these performances closely and in its original way. At the heart of this rich tradition, three main show forms have a special place: New Theater (NOH), Kabuki and Bunraku. Each of these species has its own executive and aesthetic style and is also a reflection of social structures, cultural values and historical developments in Japan.

New theater is known for its slow movements and mysterious face -to -face, Caboki performances with its high -profile performances and Bonrako with its sophisticated puppet techniques, each of which is a unique combination of art, music, literature and religious rituals. Given Japanese culture, known as its particularity, studying Japanese theater is one of the best ways to find out how theater has expanded in the context of various cultures.

In this article, we will examine and introduce each of these three main forms of Japanese theater: their historical background, their dramatic and aesthetic characteristics, their differences and similarities, and their role in Japanese cultural heritage and society.

New Theater (NOH): mysterious, inhabited, mythical

The new theater had a long history, but in the fourteenth century Kan’ami and his son Zeami officially established its identity as a new art form and peaked in the Muromachi period (1 to 2). This style of Japanese theater is known for its slow -motions, traditional music, smileys or wooden masks and poetic texts. New is not a play, but a kind of ritual formalities; A minimalist journey in the realm between the world of the dead and the living.

In the structure of a new play, usually the main character, or “shite”, is a mythical spirit, goddess or hero that encounters a monk or traveler or Waki. The play is performed in two parts: Shabite first appears in a human form and narrates its past, then in the second part, it returns with its true appearance and reveals the hidden truth of the story. The narratives are often based on myths, Buddhist texts or classic poems.

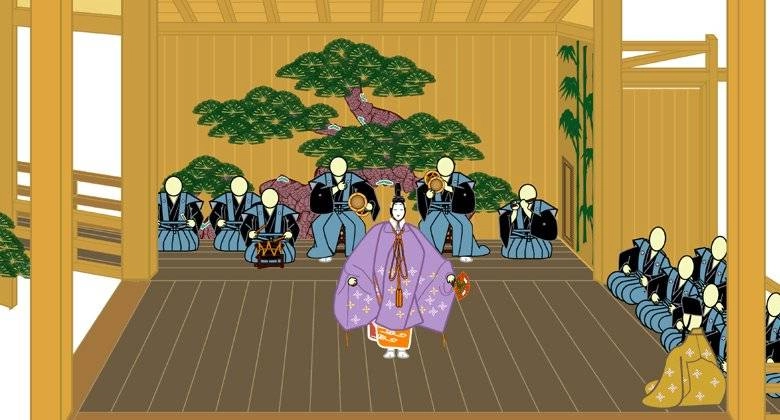

Some of the scene of the new theater performance. In the center: Shita / In the front, right: Vake / Eighty Group Right: Giotai (Chorrons or Cooperatives) / Four Back -ups in the Middle and Right: Musicians / Two Back -ons on Left: Scene Assistants

Music in New Theater is of great importance. Drum musicians (Kuzsuzumi, Otsuzumi, and Tiko) and Flute (Nawan), along with chorus bands, create an audio space that helps to create a mystical and surreal mood. Music both emotionally sets the scene, and gives the actor a clue to express the inner state of the personality.

One of the unique features of the new theater is the use of noh-men, which puts Shaba or the main actor on the face. These masks identify the appearance of the personality and, with the slightest change in angle, are capable of transmitting a spectrum of emotions. The skill of the new theater actor is to bring the soul to the mask and transfer to the audience by slowly moving the head and body.

Overall, with the emphasis on the actor’s physical language, the creation of a minimalist space and a religious/mythical attitude to life and death, the new theater is a kind of aesthetic meditation that is rooted in ancient traditions and is still living in Japan, though its audience is limited.

Kabuki Theater (KABUKI): Playing Playing Color and Movement

Caboki, unlike the new atmosphere, solitude and new minority, is the crystallization of Japanese theater at the height of being colorful, vibrant and popular. This style of theater emerged in the early seventeenth century and the Edo period (1 to 2) and quickly became popular among the middle classes. Its founder, Izumo No Okuni, was a woman from Kyoto who created a new form of dramatic art by combining the art of dance, acting and religious plays.

From the very beginning, Kabuki had a bold and energetic look at social, historical and even political issues. Caboki’s performances of heroes and anti -heroes, tragic lovers, dedicated samurai and cruel conspirators were in the context of narcissism. Caboki shows have three main subdivisions:

- Jidaimono: Pictures on Historical Events

- Sewamono: Pictures about people’s daily lives

- Shosagoto (Shosagoto): Dance -focused shows

Or the difference between the subject, each of them is mixed with exaggerated, fantasy and often comedy elements.

800,000

720,000 Toman

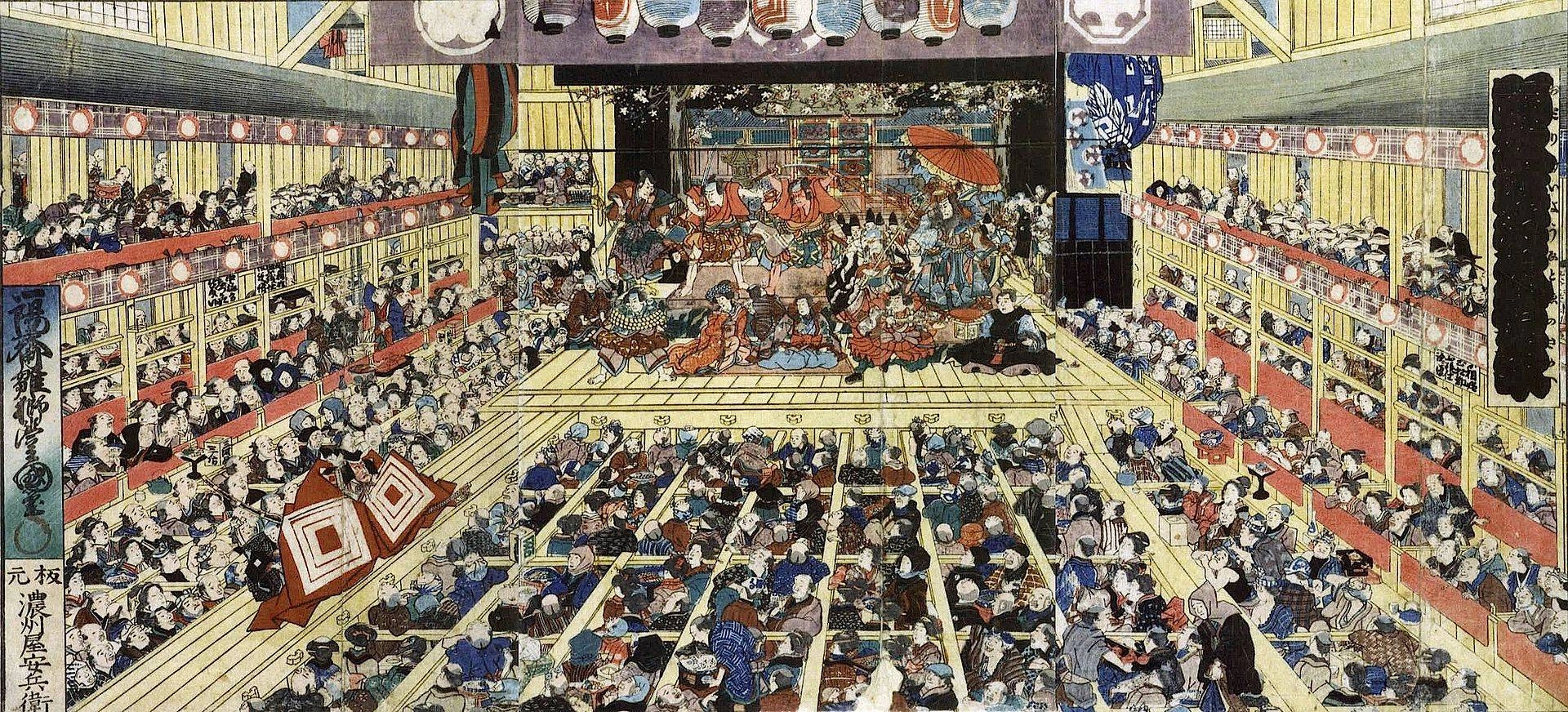

The Fermi features of Caboki have made it one of the most visual and dynamic species of Japanese theater. Caboki’s scene is usually equipped with a moving bridge (Hanamichi) on which the actors move through the audience, and the scene (Mawari Botai) is also responsible for quickly replacing the decor and diversifying space.

In Kaboki’s performances, male actors play all the roles, even female characters (Onagata), and this restriction has not even been lifted to this day, though the ironic and perhaps sad thing is that Caboki’s theater was created by a female group for the first time. The actors in this theater, skillful in body language, tone, exaggerated drama movements, and specific figures, can almost play a role. The face -to -face face style, with color lines that signify the moral characteristics of the personality, is one of the most prominent Caboki’s appearance.

A painting of the performance of the Shibaraku Caboku play in Year 2. Compare the crowd of Caboki with a new solitude.

Another important element of Kabuki is the live music of the performance that is played with instruments such as Shamisin, Koto, and sometimes percussion instruments. This music, along with traditional voices (now connected to the stereotype of the Eastern space), presents a special drama to each scene. Also, “MIE” is one of the symbolic movements of Kabuki in which the actor in the middle of the scene stops in a constant and exaggerated state and stare at the audience in silence, as if he had a moment full of glory or anger.

Over the centuries, Kabuki became a symbol of Japanese national culture. Although there were restrictions on certain historical periods, including the Miji period, today, despite some modernization, it is still in its traditional format in the prestigious Tokyo and Kyoto venues and is listed in the UNESCO Cultural Heritage List.

Burnaku Theater: Dolls with the Human Spirit

Bonrako, one of the most amazing forms of traditional Japanese theater, is an art in which dolls, with stunning skills, showcase life and emotion. This kind of play emerged in the Osaka region in the seventeenth century and at the same time as Kabuki’s flourishing and became one of the most sophisticated puppet shows in the world.

The main feature of Bonrako is the precise combination of three dramatic elements: puppets, narrators (Taio) and Shamison musicians. Each of these elements has a fundamental contribution to the formation of the viewer’s experience. Contrary to what is common in other puppet shows, in Bonrako, puppets are fully seen on stage. Each doll is guided by three people: one right head and right hand, the second left hand and the third legs. The coordination between the three puppets is the result of years of strict practice and practice that focuses on directing precise and harmonious movements.

The narrator or “Taio”, which usually sits on the platform and provides all the dialogues and descriptions for all characters. His tone, sound, rhythm, and emotional expression transmits the inner mood of the characters and builds the heart of the narrative. Next to him, a Shamisinist sits, with his three -month instrument playing the soundtrack and flowing with the narrator, rhythm and tension of the story.

Bonrako dolls are almost as much as human half -size, and their facial, eyes, mouths and eyebrows are mechanically designed to express emotion with dramatic elegance. The dresses and appearance of these dolls are often made of great accuracy of traditional and traditional fabrics and have signs of social status, gender or cultural origin of personality.

The musicians have given an important role to play in the spirit of Bonrako.

Bonrako themes are often similar to Kabuki: tragic romance, Samurai -based stories, or family adventures. But what distinguishes Bonrako is its deep and narrative -based emotional approach. Stories such as “The Love Suicides at Amijima” or “The Courier for Hell” are examples of Bonrako’s influential drama that portray the characters with poetic pay.

Like Nov and Kabuki, the Bonrako Theater has faced challenges in various historical periods, but is still being performed in a traditional format. Today, the Bonrako National Hall in Osaka is one of the main centers of its implementation, and the art is listed in the UNESCO Cultural Heritage List.

Comparative comparison between Nodes, Kabuki and Bonrako

Traditional Japanese theater, with three main branches, Kabuki and Bonrako, presents a comprehensive picture of its aesthetics, beliefs and cultural changes. Each of these species has its own style and structure, and represents a range of tastes, social classes, and philosophical attitudes.

In terms of aesthetics and performance, new theater, with its simplicity and minimalism, emphasizes stagnation, symbolism and spirituality. The almost empty scene, the slow movements of the actor, and its mystical music encourages the audience to end. On the opposite point, the cable is full of color, motion, sound and exterior display. The design of the scene of the highlights, the exaggerated arrangement of the actors and the dramatic effects make it a very visual display. Bonrako also focuses on the technical skills of puppetry and narrative, a place between the two: it is neither simply new nor as high as Caboki.

In terms of actors’ participation and narrative, new is closer to individual performance; The characters and the roles are often masked. In Kabuki, the actors have a central role, especially the actors who play the role of women (Engata). In Bonrako, the interaction between three people to control each doll, along with collaborating with the narrator and musician, is a collective experience.

In terms of social audience and social function, the main audience of the noblemen and religious authorities was, while Kabuki and Bonrako had spectators among the middle and public classes, and even the aristocrats had a humiliating view of these plays, and their venue. These differences indicate Japan’s cultural diversity and reveal the interaction between tradition and innovation in the context of performing arts.

What role did the Japanese theater play in the power structure?

Traditional Japanese theaters have always been a reflection of the social and political structures of their time. For example, the new theater had aristocratic and religious roots, Kabuki had a popular origin Bonrako promoting a kind of ethical worldview, and each had a unique relationship with social power and order.

The new theater, due to the support of the military and aristocrats, became a form of formal art, court and elitist, which was closely linked to Shintoism and Zen Buddhism – two main Japanese religions. Its themes were often narratives of the ghosts of warriors, elders, and deceased, which was implemented in a quiet and minimalist structure; It is as if political authority had been reflected in artistic contemplation.

In contrast, Kabuki has always been under the control of the government despite its popular origin. Severe censorship, restrictions on female actors, and emphasis on ethical and loyal public plays, show that the government saw Kabuki as a threat to itself and the means of guiding public opinion. Therefore, sometimes in the heart of the glorious stories of Kabuki, there were hidden criticism of social inequality or corruption, though under humorous or exaggerated masks.

Bonrako, which was often performed for the urban middle class during the Edo era, specially highlighted the tension between the individual and the power. Chikamatsu monzaemon plays are often tragedies about ordinary people who make painful choices against social structure, law or ethical norms. This theater offered a deeper and more humane criticism of the constraints of society in the language of the dolls.

Source: DigiKala Meg

RCO NEWS