Scientists are testing to see if drugs based on the GLP-1 hormone can help reduce cravings for cigarettes, alcohol, and opioids, as well as food.

According to RCO News Agency, Last April, neurologist Sue Grigson received an email from a man who detailed his years-long struggle to quit addiction, first to opioids and then to the same drug prescribed to help him quit.

According to Nature, this man had come across Grigson’s research showing that certain anti-obesity drugs could reduce rats’ addiction to drugs such as heroin and fentanyl. He decided to try addiction again, this time while taking semaglutide, a drug based on the best-selling GLP-1 hormone, also known as Ozempic.

“That’s when he wrote to me that he was off drugs and alcohol for the first time in his adult life,” says Grigson, who works at the Penn State University School of Medicine.

Why do anti-obesity drugs treat other diseases?

Stories like this have spread rapidly over the past few years, through Internet forums, weight loss clinics and news headlines. These stories describe people taking diabetes and weight-loss drugs like semaglutide and Mounjaro suddenly being able to quit long-term addictions to smoking, alcohol, and other drugs, and now clinical data is beginning to back this up.

Earlier this year, a group led by University of Southern California psychologist Christine Hendershott showed in a randomized trial that weekly injections of semaglutide reduced alcohol consumption, a key piece of evidence that GLP-1 drugs can alter addictive behavior in people with substance use disorders. More than a dozen randomized clinical studies are currently underway around the world investigating the effects of GLP-1 drugs on addiction, and some results will be published in the coming months.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists are investigating how weight-loss drugs curb addiction by affecting hormone receptors in areas of the brain that control cravings, rewards and motivation. They find that GLP-1 treatments help reduce cravings for alcohol, opiates, nicotine and cocaine through the same brain pathways that reduce hunger and overeating signals.

Anti-obesity drugs are not always permanent. What happens when you leave them?

The researchers caution that the research is still in its early stages. First, we need to find out if this method is effective and safe. But some researchers and doctors are excited. Elizabeth Gerlag Helm, an addiction biologist at the University of Gothenburg, says: “In the last few decades, no new drug category for the treatment of addiction has been approved by authorities.” If GLP-1 drugs prove effective in larger trials, this would be a breakthrough.

From the laboratory to the public stage

It took several years for the current hype surrounding GLP-1 drugs to treat addiction to develop. Researchers first developed them to control blood sugar in people with type 2 diabetes. It wasn’t long before it became clear that drugs can suppress appetite and facilitate weight loss. They act on hormone receptors in the pancreas and intestines; where they help regulate blood sugar and signal satiety, and also act on key areas of the brain that control reward and motivation, reducing cravings for high-calorie foods.

In the early 2010s, Gerlag Helm investigated whether these drugs could also reduce other cravings. He published papers showing that these drugs could reduce cravings in rats addicted to alcohol, nicotine, and stimulants such as amphetamines and cocaine. His group also showed that treatment with GLP-1 can reduce relapse-like behaviors.

However, his findings received almost no attention from addiction researchers and pharmaceutical companies showed no interest.

Lorenzo Leggio, a physician-scientist at the US National Institutes of Health, was drawn to this issue and in 2015 collaborated with Gerlag Helm to uncover the first evidence of a link between the hormone GLP-1 and alcohol dependence in humans. Their group found that a common variant of the GLP-1 receptor gene was associated with drinking more alcohol.

Using postmortem human brain tissue, Leggio’s lab showed that people with alcohol use disorder had higher levels of GLP-1 receptors in reward-related areas of the brain. Leggio suspects this is an adaptive response. Alcohol reduces the body’s production of GLP-1, so the brain increases expression of the receptors to maintain sensitivity to the hormone in reward and motivation circuits, he says.

How anti-obesity drugs reduce food noise in the brain

In trials involving 20 people with opioid use disorder, treatment with liraglutide, a first-generation GLP-1 drug, reduced opioid cravings by about 40 percent, and when Fink-Jensen’s team used fMRI, activity in reward-related regions was reduced when viewing pictures of alcoholic beverages.

The tested first generation drugs are much weaker than semaglutide and tirzepatide. These second-generation compounds activate the GLP-1 receptor more strongly, last longer in the body, and have shown greater benefits in a wide range of health conditions. Therefore, these new drugs may change the behavior of people with substance use disorders.

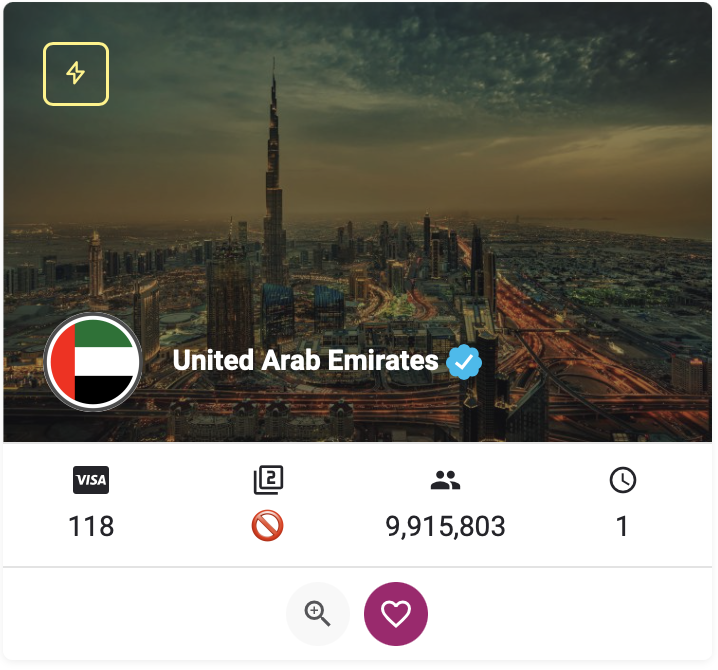

How miracle drugs are changing the world

By affecting common reward and motivation circuits, GLP-1 drugs could theoretically target any type of addiction and even help people who use multiple drugs. Also, the connection between GLP-1 and reward has inspired interest in the treatment of cognitive and psychiatric disorders; Because the same brain circuits that support reward processing also support learning, memory, motivation, and decision-making.

Anti-obesity drugs also reduce inflammation and can help treat depression and memory disorders.

Broader evidence and limitations

Researchers say there is still a long way to go before the legal approval of these drugs to treat addiction. They first need clear, replicable evidence from large randomized trials. Changes in brain activity or reduced cravings alone are not enough.

It must also be ensured that the effects of drugs on weight and appetite do not complicate addiction treatment, as drug users often have irregular diets. Therefore, clinical trials of GLP-1 for addiction usually include overweight or obese participants.

Big pharmaceutical companies have also entered the field and are testing semaglutide to reduce liver damage and alcohol consumption.

Success stories continue to circulate on social media, but researchers warn that changing habits may be due to weight loss, not medication.

end of message

RCO NEWS