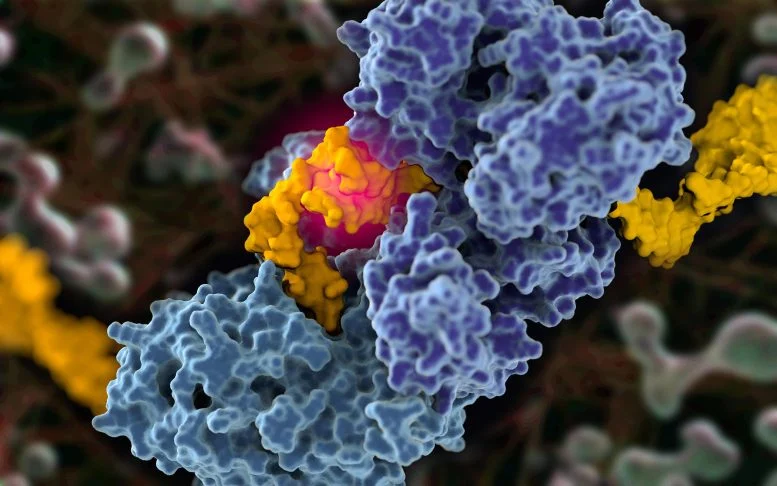

DNA repair proteins act as molecular editors of the body and constantly identify and correct the damage of our genetic code. One challenge that has long been involved in researchers has been to understand how cancer cells use one of these proteins called Pol-Tota to support their survival. Scientists have now captured the first high -resolution images of Tuta polymerase, which illuminates its role in cancer development.

According to RCO News Agency, The study, published on February 5, shows that Tuta polymerase has a significant structural evolution when connected to broken DNA disciplines. This study provides an active and active condition for the design of more accurate and effective cancer treatments by drawing active and connected to DNA polymerase.

“We now have a clearer image of how the Tutan polymerase works, which allows us to block its activity more accurately,” says Gabriel Lander.

Tutan Polymerase: A key player in the survival of cancer cells

Technically, Tuta polymerase is an enzyme. A type of protein that accelerates chemical reactions, including cell repair reactions. DNA damage is a permanent problem for cells that occur millions of times a day throughout our body.

Cells usually use very precise mechanisms to relieve these failures, but some cancers, especially cancers that result from BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, such as some breast and ovarian cancers, do not. Instead, they are dependent on an error -prone method that is controlled by theta polymerase.

Christopher Zerio, the first author of the study, a former post -doctoral researcher at Landar Laboratory, adds: “Tuta is an important goal, and many pharmaceutical companies see it as a promising way to treat cancers that have defective DNA restoration paths.”

Although previous studies have depicted parts of the Tuta polymerase structure, the enzyme interactions with the DNA were not well known.

“What was unclear was how the DNA was really involved in the development of the drug,” Zario says.

Tota Polymerase Registration at the moment of action

Previous research has shown that there are two -by -Tuta seals: the tetramer, which contains four versions of the enzyme and the dimer, which contains two versions. But why or how the Tutan polymerase changes between these forms was unknown.

Prior to this study, the Tuta polymerase structure was only in inactive mode, and a large scientific gap on how the enzyme interacted with DNA was left.

“You know that interaction happens, but without seeing it, this mechanism remains like a mystery,” explains.

The Blue Polymerase enzyme connects two parts of a broken yellow DNA. This process is a mutant and can lead to cancer.

Using Cryo’s electron microscopy and biochemical tests, the group achieved amazing discovery while registering DNA’s polymerase at the moment of DNA repair. Whenever the Tuta polymerase was connected to the broken strands, it was constantly changed from tetramic mode to a default configuration that had not been seen before.

When the Tuta polymerase was active, it repaired the DNA using a two -step process. In the first step, the enzyme searches for small sequences called “microhomologies” in broken strands. When a sequence is found, the DNA polymerase keeps the broken DNA close together so that they can be connected without the need for additional energy. Most enzymes need energy to boost energy to their performance, but Tuta polymerase relies on the natural attraction between DNA sequences and allows them to be in place.

“If we can block this process, we can make Tutan polymerase cancers more sensitive to treatment,” says Zario.

Tutan polymerase is produced at low levels in healthy cells, making it a promising goal for cancer treatment. Unlike cancer cells dependent on theta polymerase, healthy cells rely on more accurate repair mechanisms that require energy that guarantees more accurate DNA repair. Since healthy cells do not need Tuta polymerase to survive, blocking enzyme activity may not cause extensive damage to healthy tissue.

Most cancer drugs target proteins that healthy cells also need, Lander points out. Specifically, targeting Tuta polymerase should only eliminate cancer cells and reduce the likelihood of side effects during treatment.

The drugs that inhibit theta polymerase are currently in clinical tests, but now they need to be combined with other treatments to work effectively. While this study can help develop a more accurate drug, further research may show other roles that the enzyme may play in cellular functions.

The end of the message

(tagstotranslate) Cancer

RCO NEWS