To answer this question, scientists have gone to people who underwent stem cell transplants to treat leukemia more than 40 years ago to examine the rate of potentially cancerous mutations in them.

According to RCO News Agency, So far, donor hematopoietic stem cells have been used to treat hundreds of thousands of people with leukemia and other blood disorders.

Ever since the first hematopoietic stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with leukemia more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they develop cancer-causing mutations.

Now a unique study of the longest-lived transplant recipients and their donors has shown that people who receive donated stem cells do not appear to have an increased risk of developing such mutations.

Michael Spencer Chapman, a hematologist at the Barths Cancer Institute in London, says: Our results are surprising and at the same time reassuring.

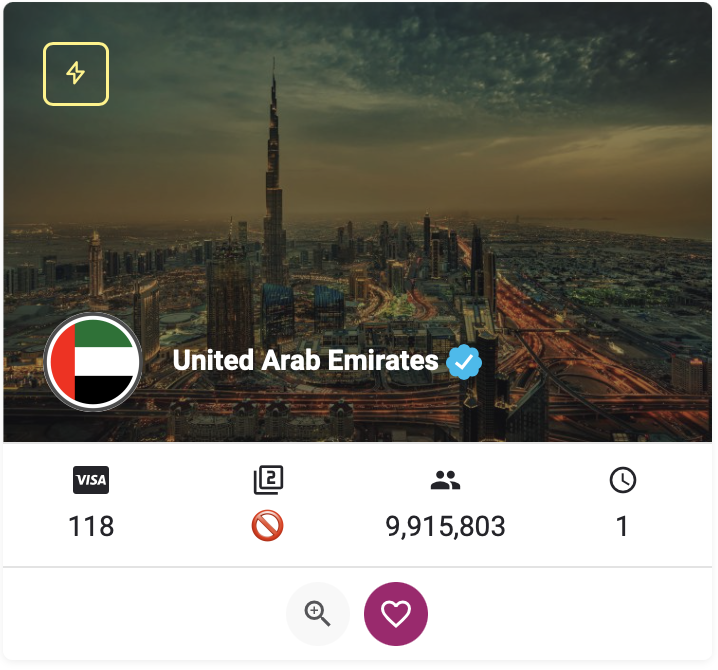

Alejo Rodriguez-Fraticelli, a stem cell biologist at the Biomedical Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, also says: This is great news for people undergoing these treatments.

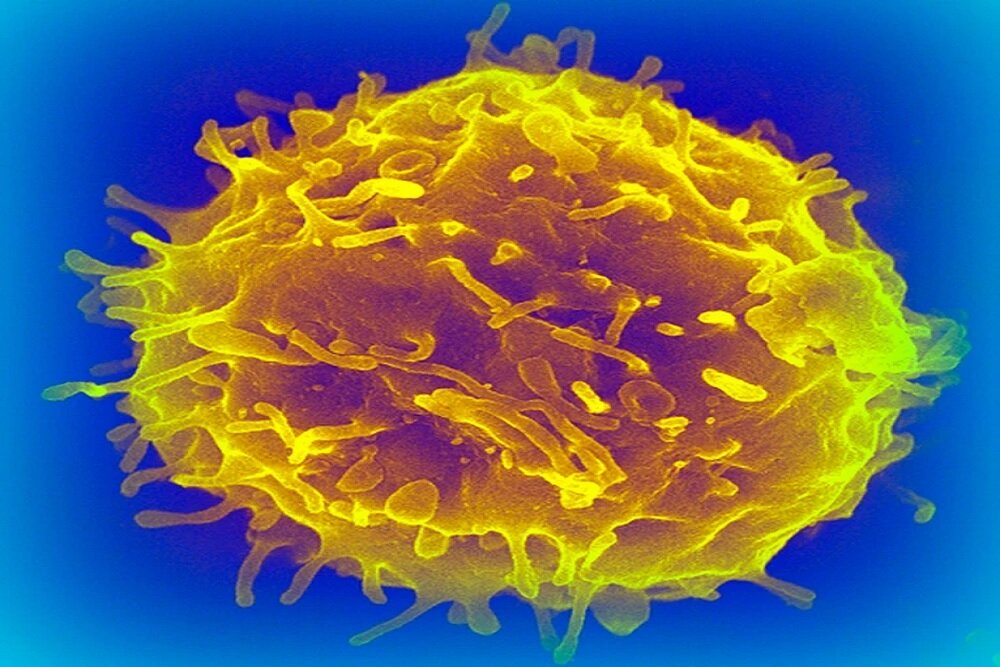

Hematopoietic stem cells are precursor cells located in the bone marrow that give rise to all types of blood cells. They have been used to treat hundreds of thousands of people with leukemia and bone marrow diseases.

These transplants involve draining a person’s entire blood supply of stem cells and replacing them with cells from a healthy donor, but researchers have long worried that putting the cells under such pressure could increase the risk of cancer.

It should be mentioned that in rare cases, in one case out of every 1,000 transplants, donor cells turn into cancer in recipients.

The study of mutations

The latest study, published this week in the journal Science Translational Medicine, looked at mutations in specific genes associated with cancer. It was thought that these mutations could give the hematopoietic cells in transplant recipients a growth advantage, allowing them to divide and multiply rapidly as the recipient ages, eventually developing into leukemia.

Some of the first transplants were performed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in the late 1960s. In 2017, Masumi Ueda Oshima, a clinical researcher who studies post-transplant aging at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, and her colleagues decided to contact transplant recipients and their donors to collect transplant samples. Compare blood and how cells age. “It was a really big exploratory journey,” he says.

The team collected blood samples from 32 individuals, including 16 donor-recipient pairs, who received their transplants between 7 and 46 years ago. The researchers used a highly sensitive technique to sequence genes known to obtain mutations associated with bone marrow cancers.

The team found cells with the mutation in all healthy donors, even those as young as 12 at the time, and found that the older the donor, the more mutations were present in their blood, but overall the rate remained low. It is about one in a million pairs.

The researchers then compared mutation patterns in 11 donor-recipient pairs who had access to donor blood samples from the time of the transplant. They found similar mutation patterns in both groups.

On average, mutations occur at a rate of 2 percent per year in donors and 2.6 percent per year in recipients, the researchers said.

“Surprisingly, there are very few mutations in the stem cells created through the transplant process,” says Spencer Chapman. This suggests that cells in transplant recipients age at the same rate as their donors and do not increase the risk of developing mutations that may predispose them to leukemia.

The fact that mutation rates remain stable long after transplantation suggests that the regenerative capacity of the hematopoietic system is truly profound, says Oshima.

Frattichelli also says that while the results are reassuring, they are based on a small number of people, making it difficult to draw general conclusions.

The complexity of aging

Spencer Chapman observed similar results in a separate study of donor and recipient pairs. His study included 10 transplant recipients who had received hematopoietic cells from their siblings between 9 and 31 years earlier.

They didn’t just look for changes in specific cancer-related genes, they extracted and grew hematopoietic cells and sequenced the entire genomes of individual cells.

They ended up finding that the recipients had, on average, only slightly more mutations than their donors and only 1.5 years of extra natural aging, a finding similar to Oshima’s.

When he and his colleagues looked specifically at mutations that give cells a growth advantage, they found that cells with just one of these mutations were found at similar levels in recipients and donors, but cells with two or more of These beneficial mutations were present at higher levels in recipients than in donors. This could explain why, in rare cases, transplanted cells can turn into cancerous tumors.

Spencer Chapman says more work and research is needed to better understand the implications of these aging processes in terms of cancer risk and immune system function.

Both studies could have implications for people receiving stem cell transplants and blood-based gene therapies, for example, to treat sickle cell disease.

Spencer Chapman says more and more of these treatments are being developed and are being done on children, who will have to rely on transplanted cells for the rest of their lives.

end of message

RCO NEWS