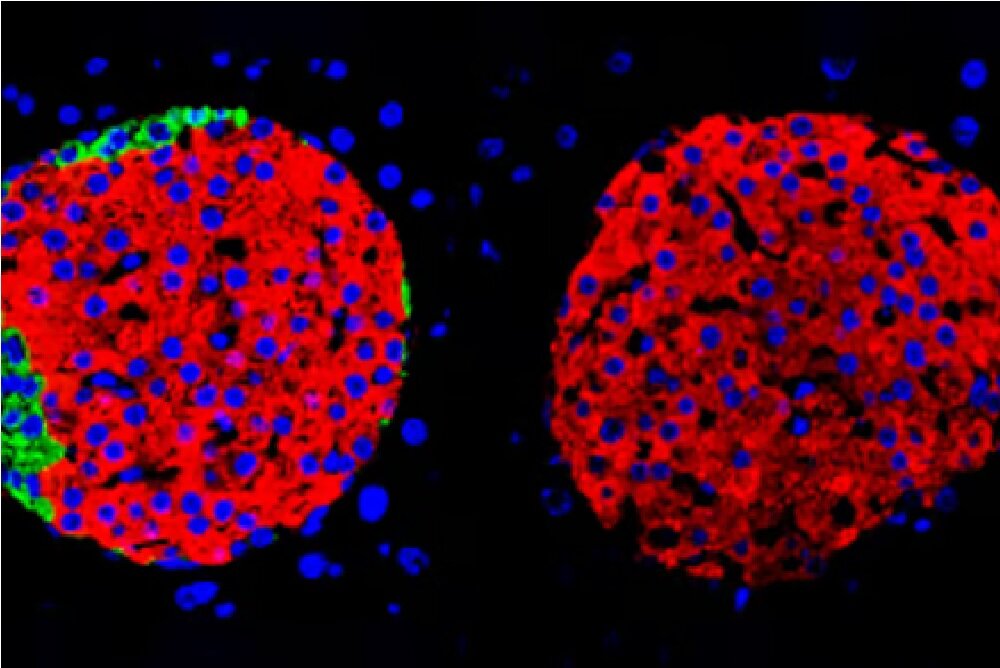

New research has shown that pancreatic cells can work on their own when it comes to producing insulin.

According to IsnaAccording to new research, beta cells in the pancreas do not need the help of other pancreatic cells to produce insulin.

These findings are not only a potential game changer for diabetics, but challenge long-held assumptions about how the body produces insulin.

Healthy beta cells in the pancreatic islets produce insulin in response to a rise in blood glucose after eating. However, if the beta cells are not working properly or are destroyed, producing little or no insulin, diabetes develops.

Until now, it was accepted that beta cells do not work alone, but together with other hormone-producing pancreatic cells, namely alpha, delta and gamma cells, to maintain blood glucose levels. However, a new study by researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) in Switzerland has challenged this common belief.

Professor Pedro Herrera from the Department of Genetics and Developmental Medicine at UNIGE and co-author of the study says: Until now, it was thought that the differentiated adult cells of an organism could not functionally regenerate and reorient themselves. Therefore, pharmacological stimulation of this cellular plasticity could be the basis of a completely new treatment for diabetes. But what happens if all the endocrine cells of the pancreas abandon their original function and start producing insulin? This is what we wanted to know in our new study.

Herrera and colleagues discovered in 2010 that if beta cells die prematurely, pancreatic cells responsible for producing other hormones such as glucagon, which counteracts the effects of insulin to raise blood glucose, are produced by alpha cells, or somatostatin, produced by delta cells. and is a strong inhibitor of insulin secretion, it can start to produce insulin.

In the current study, they investigated whether non-beta cells are also necessary for insulin production.

To confirm this, we generated mice in which all non-beta cells in the pancreas could be selectively removed when they reached puberty to see how the beta cells were able to regulate glucose, said Marta Perez-Francis, a member of the research team. are blood (blood glucose). Surprisingly, our mice were not only able to effectively manage their blood sugar levels, but were even healthier than the control mice.

The researchers found that almost total loss of non-beta cells did not affect the mice’s feeding behavior, body weight or blood glucose control, even when they were fed a high-fat diet. In fact, when they examined slices of the pancreas and isolated groups of cells composed of beta cells, the researchers found that they exhibited the same insulin secretion dynamics as normal pancreatic islets, which contain alpha, beta, delta, and gamma cells.

Mice with beta cells showed sustained improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance that were absent in human diabetics in all target tissues, especially adipose tissue.

“There’s an adaptation process where the body recruits other hormone cells from outside the pancreas to deal with the sudden drop in glucagon and other pancreatic hormones,” Herrera says. But this clearly shows that the non-beta cells of the pancreatic islets are not necessary to maintain glycemic balance.

While it is still early days of this research, the findings of this study could be a game changer for people with diabetes. For example, it may be possible to generate new beta cells from stem cells and then transplant them into patients.

Herrera concluded: “Our results prove that cell-targeting strategies for insulin really can work.” Therefore, the next step of our work involves creating molecular and epigenetic characteristics of non-beta cells from diabetic and non-diabetic individuals in the hope of identifying elements that can cause the transformation of these cells in the pathological context of diabetes.

This study was published in the journal Nature Metabolism.

end of message

RCO NEWS